Government spending plays a powerful role in shaping inflation, even though its effects are not always immediate or obvious. When governments increase spending, they inject money into the economy supporting growth, jobs, and public services. But if spending grows faster than the economy’s ability to produce goods and services, it can also contribute to rising prices.

Understanding how government spending impacts inflation requires looking at demand, supply, financing methods, and timing rather than assuming spending automatically causes price increases.

The Basic Link Between Spending and Inflation

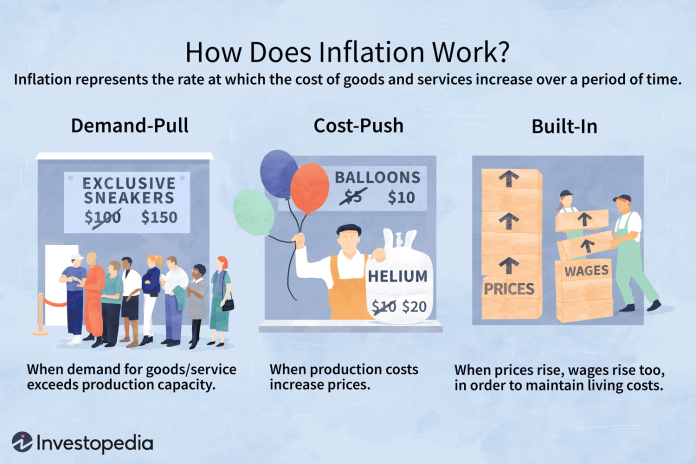

Inflation occurs when overall demand in an economy exceeds its supply capacity. Government spending directly affects this balance. When the government spends more on infrastructure, social programs, defense, or stimulus checks, it increases demand for labor, materials, and consumer goods.

If the economy has unused capacity such as unemployed workers or underused factories this additional demand can boost output without causing much inflation. Problems arise when spending floods an economy that is already near full capacity, pushing prices higher instead of increasing production.

Demand-Pull Inflation and Government Outlays

One of the clearest channels through which government spending impacts inflation is demand-pull inflation. Large spending programs raise household incomes and business revenues, encouraging more consumption and investment.

When demand surges faster than supply can respond, businesses raise prices. This effect is most visible during periods of strong economic recovery, when government stimulus coincides with rising consumer confidence and limited productive slack.

Supply Constraints and Spending Pressures

Government spending also affects inflation through supply-side limitations. If increased public spending competes with the private sector for scarce resources—such as skilled labor, energy, or raw materials it can drive up costs across the economy.

Infrastructure projects, defense contracts, and large public works programs can create bottlenecks, especially if supply chains are already strained. These higher costs often get passed on to consumers as higher prices.

How Deficit Spending Amplifies Inflation Risks

When government spending exceeds tax revenue, the resulting deficit must be financed. Borrowing is the most common method, but how deficits are funded matters for inflation.

If borrowing absorbs private savings, inflationary pressure may be limited. However, if deficits are indirectly financed by creating new money especially when central banks purchase large amounts of government debt the increase in money supply can intensify inflation.

This dynamic gained attention during periods of aggressive fiscal stimulus combined with accommodative monetary policy.

The Role of Monetary Policy in Offsetting Spending

Government spending does not operate in isolation. Central banks respond to fiscal policy by adjusting interest rates and liquidity conditions.

If policymakers believe spending is overheating the economy, they may raise interest rates to cool demand. Higher rates slow borrowing, reduce spending, and help contain inflation. When monetary policy counteracts fiscal expansion, inflationary effects are often muted.

Inflation tends to rise fastest when government spending expands while monetary policy remains loose.

Temporary vs Persistent Spending Increases

Not all government spending affects inflation equally. Temporary, targeted spending especially during recessions often fades before long-term inflation takes hold. Persistent, large-scale spending increases, particularly without matching revenue sources, pose greater inflation risks.

Markets pay close attention to whether spending is one-time or structural. Long-term spending commitments increase expectations of higher future inflation, which can influence wages, pricing decisions, and interest rates today.

Expectations and Inflation Psychology

Inflation is partly driven by expectations. If businesses and consumers believe higher government spending will lead to sustained inflation, they may adjust behavior in ways that make inflation self-reinforcing.

Workers demand higher wages, firms raise prices preemptively, and investors demand higher yields. These expectation effects can amplify the inflationary impact of spending even before shortages fully materialize.

Government Spending During Crises

During economic crises, government spending often rises sharply to stabilize markets and protect households. In such cases, inflationary effects may be delayed or absent because demand is weak and unemployment is high.

Problems emerge later if emergency spending remains in place after recovery or if supply remains constrained. Inflation pressures tend to build when crisis-era policies persist into expansion phases.

Why Government Spending Does Not Always Cause Inflation

History shows that government spending alone does not automatically trigger inflation. Countries with strong productive capacity, flexible labor markets, credible institutions, and well-managed monetary policy can absorb higher spending with limited price pressure.

Inflation depends on context: economic slack, productivity growth, global trade conditions, and central bank credibility all matter.

The Long-Term Inflation Trade-Off

Over the long run, persistent deficit spending can reduce confidence in fiscal discipline. If investors worry about debt sustainability, borrowing costs may rise, weakening currency values and adding inflationary pressure.

Sustainable spending that supports productivity such as education, infrastructure, and technology—can actually reduce inflation risk by increasing supply capacity. Poorly targeted or inefficient spending does the opposite.

What This Means for Households and Investors

For households, the inflationary impact of government spending shows up in everyday costs like food, housing, and energy. For investors, fiscal policy influences interest rates, bond yields, stock valuations, and currency markets.

Monitoring government budgets alongside central bank actions provides a clearer picture of future inflation risks than focusing on spending alone.

Conclusion: Government Spending as an Inflation Force

Government spending can fuel inflation, but it does not do so mechanically. Its impact depends on timing, scale, financing, and economic conditions. When spending boosts demand without expanding supply or when it coincides with loose monetary policy inflation risks rise.

When managed carefully and coordinated with monetary policy, government spending can support growth without destabilizing prices. The challenge lies in knowing when stimulus becomes excess, and when support becomes strain on the economy.